Defender – ever the hero

/The geriatric Defender, that long-serving and immeasurably accomplished utility vehicle, is the last and best of the breed. A final drive reinforces why it needs to go – and why it will always be missed.

For: An automotive icon dripping with charisma.

Against: Doesn’t suffer fools.

Score: 4.6/5

IT’S set to be the oldest ‘new’ car ever tested by this outlet. Why bother?

Because of what it is. What it represents. Because death is near. In just a few weeks, the Reaper’s scythe will finally fall on a British motoring stalwart born of a lineage dating directly back to the brand’s beginning in 1948.

Ever-more-stringent EU emissions regulations are the killer blow but safety shortcomings were also overwhelmingly obvious: An aged design trapped in the – gosh, 80s, 70s, 60s? – has no time for truly modern safety aides.

While no-one with any ounce of sanity could surely argue that the Defender cuts the mustard any longer for performance or practicality - at that level, it’s just not very good – it is still one of the greats. An antiques roadshow with huge presence and charisma celebrated by owners, including Queen Elizabeth II, who have special loyalty going beyond mere possession toward a vehicle called “as cantankerous as a donkey, as loyal as a dog.”

Keeping that x-factor alive is why plans for an all-new car have been repeatedly pushed back and why previous design studies have never been allowed out of high-security styling studios.

Yet apparently a decision has been made. Late next year a new unibody full-size Discovery arrives, delivering a modern chassis construction is lighter and more rigid and easier to engineer for crash standards, as well fuel economy and emissions regulations.

With the $63,000 manual 90 wagon here being the last of the last, the final import for promotional use brought in by Land Rover New Zealand, it was now or never to have one last run.

This British Army green example was straight from the box save for the addition of a big brawny winch that, while superfluous to the city professional types - architects, doctors, advertising agency folk, the lady on the Youi ad – who comprise the major clientele now that the country and much of the military have turned their backs on this beast of burden, is nonetheless considered a must-have, because the current fanbase does seem to love to dress up their Landies.

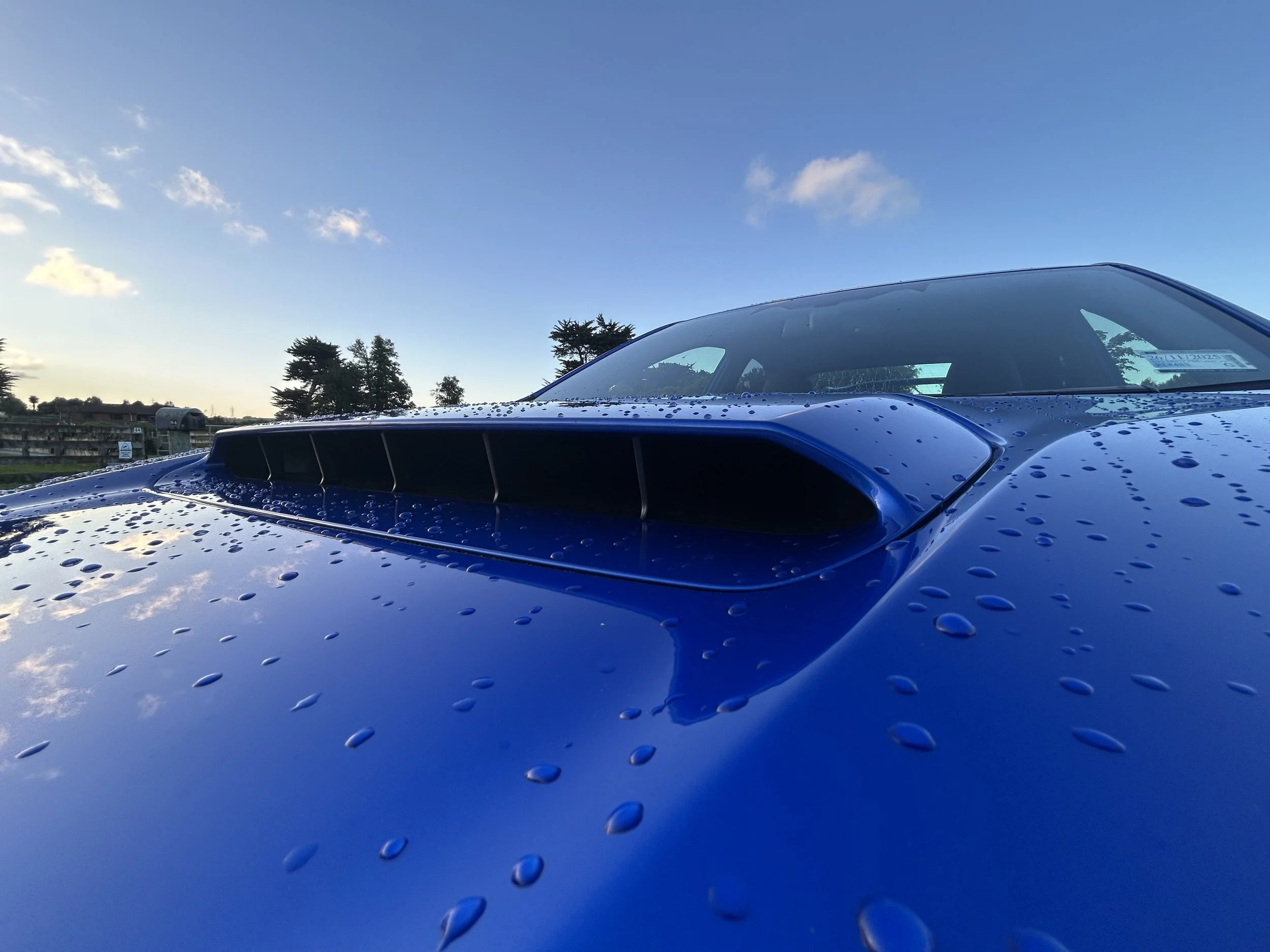

Countys and Defenders now take as standard those unpainted grid pattern alloy plate epaulettes atop the front wings – actually designed as paint-saving hardpoint footplates – while bonnet snorkels that will never prove their worth in a river crossing, roof cages that will never hold spares and rucksacks and rear ladders that will never be ascended have become irresistible in-vogue jewellery for a customer base presumably nonetheless genuinely perplexed about why their vehicle has a second, stubby ‘gearstick’ alongside the regular one.

Actually, I know about transfer boxes and the like. But, then, I live in the country – not actually on a farm but next door to two, so it’s kinda the same thing - and since boyhood I’ve always had a real thing for Defender. I’ve driven it in the burbs (awful) and in the bush (amazing). So this ‘test’ is more a final fling, a chance to say goodbye and pass on a few observations. And it’s not really a critique, because what’s the point? Defenders are too old to have faults. Rather, they evidence traits, nuances and quirks.

Styling, image:

HERE’S a test: Ask any child old enough to hold a crayon to draw a car and chances are they’ll come up with the silhouette of this vehicle. Likewise if you ask a youngster to make a vehicle out of Lego. Again, odds are that they ‘do’ a Defender.

Well, it’s the simplest shape in auto-dom, right? A T-square sorted shape with utterly no airs or graces, sod all curves and the aerodynamics of a half brick. A lot of modern sports utilities are monococques, neaning they have car-like structures. The Defender is built like a truck (and a Model T Ford) in having a sturdy steel ladder chassis to which the ripply, flat-panelled aluminium riveted body is attached. Just like a WWII Jeep? Exactly. The Wilkes brothers had the eminently British idea of taking that legend and improving it.

It looks starkly utilitarian and very old, but to my eyes it still looks good: Obviously from another time yet still timeless. But there’s no argument that it has looked the same for a long, long time. It’s a mistake to think the shape has never undergone change. Maybe the tail lights and finger-snagging rear door latch are just like those on the original Series I of 1948, but this isn’t the same face as was presented in those post-war years and neither are they the same panels.

Even the name isn’t as old as you might think; although the basic design dates back 67 years, the Defender name was actually not universally applied until 1990 (though there’s argument that it can logically be applied to all Series III versions with the coil spring suspension, largely ex-Range Rover, that replaced leaf springs in 1984, the last major change for the chassis).

The interior is patently just as dated, but the last ‘big’ refit back in 1998, which delivered 700 changes, looked at making improvement to comfort. That’s when it took various bits from the current (dash, air con) and previous (rear-most seats) Discovery; even an iPod socket. No-one is sure which of the 60 military forces who supported this car back then requested that.

I love that even the new stuff manages to be kooky. Example: A heater and air con system that requires two sets of controls – and two fans – that appears to have just two settings: Sahara or Siberia. The air con’s semi-independence explains that strange whirring noise you might continue to hear when the ventilation is turned off. It’s the a/c fan, which has a separate switch.

This model also offered a fancy Alpine stereo providing real depth of sound and clarity seemed a waste; even with the volume at a high setting the beautifully-modulated sounds could barely be heard at 100kmh, such is the mechanical din. The system also offered Bluetooth phone connectivity that I simply couldn’t fathom but, again, with so the car making so much of a din on the move, I doubt that it would have been that useful.

Even with the upmarket stuff, the Defender still has a spartan interior that will come has a shock to those used to modern cars, but it’s in keeping with the primary purpose for every fixture and material to have a robust look and feel that bodes well for that next Amazon expedition. Which is why David Attenborough, longtime voice of BBC Nature, drove one. So too did the British Special Air Service when in the deserts of Iraq.

Powertrain, performance:

Under that stubby bonnet is a noisy, rattly Ford Transit van derived 2.2-litre turbo-diesel four-cylinder that makes 90kW at 3500rpm and 360Nm at 2000rpm, figures that hardly astound in this day and age and, in fact, weren’t that impressive even when this engine was homed into this model around a decade ago.

Going the Trannie route was to reduce emissions and that target has been achieved, insofar that it is not so smoggy as to be illegal. Yet with a rating of 269 grams per kilometre, it is hardly Prius-like pure, either. Even though it now boasts a diesel particulate filter to cut out the worst of those emissions, you’ll be able to spot a Defender convention by the enveloping exhaust cloud.

It knows how to burn fuel, too. A combined 10 litres per 100km being the same sort of economy one can now get from an eight-cylinder turbodiesel while the latest V6 engines out of Germany are down in the sevens. The 0-100kmh time is a leisurely 15.8 seconds and it can’t even top 160kmh, either, unless in freefall having been driven it off a big cliff.

This definitely isn’t a performance car and, though the engine is tuned to provide torque foremost, it really isn’t that muscular by today’s standard. To mask this, the gearing of Defender’s six-speed manual is quite short in the lower ratios; in road driving, you’re through first and second gears – double-declutching to ensure a smooth transfer – in less time than it takes to read this sentence. However it is a remarkably sturdy engine, with an oxen-like pull generated at very low revs.

Driving appeal:

It all comes to down to where you are and what you are doing; in some respects, the better the road condition, the less impressive the Defender feels.

Conversely, point it up a paper road or across a rocky river bed and, though hardly comfortable, it will impressive with incredible adeptness. Just as you’d expect with a vehicle conceived with agrarian intention.

But, yeah, I just cannot quite conceive how the on-road demeanour or performance could be considered a particular selling point. The reason why so many Defenders seem to be driven so sedately along even relatively easy-going main roads isn’t that the occupants prefer to sit back and enjoy the scenery; it’s more to do with the fact that they’re not really that keen to up the pace beyond a certain point. Quite apart from the cacophony that comes at 100kmh, it’s also a bit of a handful because the off-road biased suspension and knobbly tyres. The chassis, with its solid rear axle, probably couldn’t take much more pace than the legal limit.

This is very firmly old-school motoring. You need to take everything you have known and learned about driving a modern car and throw it out of the window. It generally feels friendly, but always demands your utmost attention.

The car will bounce and buck even when a road surface seems perfectly flat, while the level of the understeer flops from mild to wild depending on how quickly you’ve tried to pour it into a corner.

The big wheel and elbows-out driving position is potentially throwback to the muscle-building time before power steering when additional leverage was required to effect cornering.

While there is power steering, its ancient worm-and-roller mechanics mean that there is little to no connection between your physical input and what the car is doing; it is so vague and slow and with a lack of self-centring that you even have to turn the steering lock back off once you’re round a corner. This and a turning circle the size of a large African country means tight turns are absolutely out of the question.

At the same token, the more rough the going gets, the more adept the Defender is. With 323mm of underbody clearance (250mm ground clearance to the axle), 47-degrees approach angle, 147-degree ramp-over angle and 47.1-degrees departure, plus a wading depth of 500mm, the Defender is as well-sorted for the worst as it has ever been.

Out at Mark Warren’s ‘Man Cave’ property in first gear low-range - with the differential lock engaged and constant throttle application to aid the operation of the traction control system - the car seemed as unstoppable as the ageing process. For the most part, you’d need to be doing something really stupid to curtail its progress – just watch our video for further evidence.

Let me just say that putting the test vehicle in a perilous position in which it teetered over a drop was a durability test I hadn’t intended, and I was most relieved that, even though it was resting on the chassis rails and hanging a rear wheel in mid-air during this situation, there was absolutely no damage.

Whether a Discovery and Range Rover, with their fancy electronic driver aides, being able to self-extricate themselves from the embarrassing situation I put myself into is a moot point, but I think not.

But it’s possible I could have avoided the situation entirely had the Defender been treated to the reversing radar and, more usefully, the rear-view camera that those cars have. Then again, in any driving situation, it’s the computer between your ears that really makes the biggest difference. Mine was definitely on the blink at that moment.

But some would say life with a Defender should be one big adventure. It begins the moment you slide behind that laughably bus-sized steering wheel, a tricky judgement for taller drivers who need to origami their way into the cabin. The driving position is awkward, due to the offset pedals and a lack of decent room; the front chairs are positioned right up against the doors. Want elbow room? Roll down the (how posh) power windows. As always for me, the driver’s seat doesn’t go back quite far enough.

The ignition is odd nowadays for much more than simply being the last in Land Rover-dom to require the turn of a key. The assembly is on the left side of the steering column; the requirement to turn it toward you to start the engine means that, inevitably, new hands almost always engage the starter motor while the engine is still running – with inevitable graunching result.

Passengers who fail to claim dibs on the front passenger seat will be dismayed by the back chairs, independent items that fold down with the pull of a few levers. Access to them is military-style, via the rear swing door then climbing up a small step. The tall glass house means the back feels light and roomy but anyone of more than medium height will be constricted for headroom. And, course, you’re quite literally sitting in the boot – the floor between and behind is where everything from rucksacks to wet dogs and dead pheasants are placed.

Crash-worthiness is a subject best avoided, like accidents themselves. That the 90 and 110 actually even have antilock brakes and traction control as well is nothing short of a miracle; it was a big step just to finally get all the seats facing forward and provide every passenger with a three-point seatbelt. Categorisation as a van saved it from a crash test, the results would not be good. Airbags are a step too far for the engineering effort and ‘crumple zones’ are called other cars.

But even in general usage the car is an OSH inspector’s nightmare: For instance, kneecap-strike is a risk for the other front seat rider; those in the back risk stubbing toes on a floor beam. That's just how it's always been.

How it compares:

Does Defender even have rivals? It’s really the Lonesome George of its ilk. The Jeep Wrangler and Mercedes G-Wagen offer similarly rugged looks and off-road ability, but they are actually newer and more complex. The only Land Cruiser in the same ilk is the 70-Series; the Prado and 200-Series wagons are in a different league. They’re better on road but perhaps not as hardy off it.

What about other Land Rovers? Price-wise, the Discovery Sport is a rival – but patently it will not survive long in places that wouldn’t even raise a sweat from the old dog. The Discovery (and full-sized Range Rovers) also have excellent off-road ability, but are more like luxury cars.

The silhouette and the philosophy of the Defender date back to land Rover’s beginnings. Its time is up, it has to go. But it will never leave us – not for years and years. Defenders are built to last the worst the world can throw at them. Which means that the cars now in the hands of people who see them as nothing more than fashion accessories will one day live on to find homes with those who truly understand what them special.

I’m saving already …