Hinckley: Swashbuckling entrepreneurs and dreamers

/A stopover city for Route 66 travellers was for 25 years competing with Detroit as America’s principal Mo’town, with Moon rising to be the biggest brand.

GRIFTERS, visionaries, inventors, entrepreneurs, swindlers, and savvy investors infused the formative years of the American auto industry with a gold rush atmosphere.

The lure of riches led government officials in towns, villages, and cities to cast caution, and often common sense, to the wind as they vied for the coveted title of motor city.

In the first two decades of the 20th century in Jackson, Michigan, more than two dozen automobile manufacturing companies would rise and fall. Companies were established in Los Angeles, Omaha, New Orleans, Memphis, Tulsa, Kalamazoo, and even diminutive Enid Oklahoma.

For a brief period, St. Louis, was a leading contender for that crown. Between 1905 and 1930 more than 25 manufacturers would be headquartered in the city. And even after Detroit claimed the throne, this ancient city on the banks of the Mississippi River continued making contributions to the industry.

After the first 300 hand-built Corvettes were produced in Flint, Michigan, manufacturing was shifted to the GM facilities in St. Louis. The first of the legendary deuce and a half 6x6 trucks produced for the military in WWII were also produced at this facility.

Of all the cars produced in St. Louis, the Moon was the most successful. And it was also the cornerstone for businesses that transformed the world, including the now legendary Ruxton, one of the first American production cars that utilized a front wheel drive configuration.

The Moon automobile played a role in E.L. Cord’s meteoritic rise to automotive tycoon at the helm of the Auburn-Cord-Duesenberg empire. Walt Disney pawned his stylish Moon roadster to finance the production of Steamboat Willie, his first animated cartoon.

The Moon Motor Car Company manufactured cars from 1905 to 1930. Until its final year of operation Moon managed to remain independent through the whole of its existence. Not only that, but the company built a name for itself based on the quality, the engineering, and the craftsmanship of its product.

The company was founded by Joseph Moon after an argument with his brother John, a partner in a wagon manufacturing business. Moon bucked the industry trend and rather than adapt a traditional buggy design instead engineered a car from the ground up.

Competition was fierce, and the price of a Moon was exorbitant. But Joseph Moon was steadfast and by 1909 was building a durable, well-engineered car at a feasible price. Sales and profits began to climb.

A few years later Moon’s son-in-law, Steward McDonald, assumed the position of vice-president of the company. He knew that the key to the company’s success was design and marketing, and so that become a focus to the point of obsession.

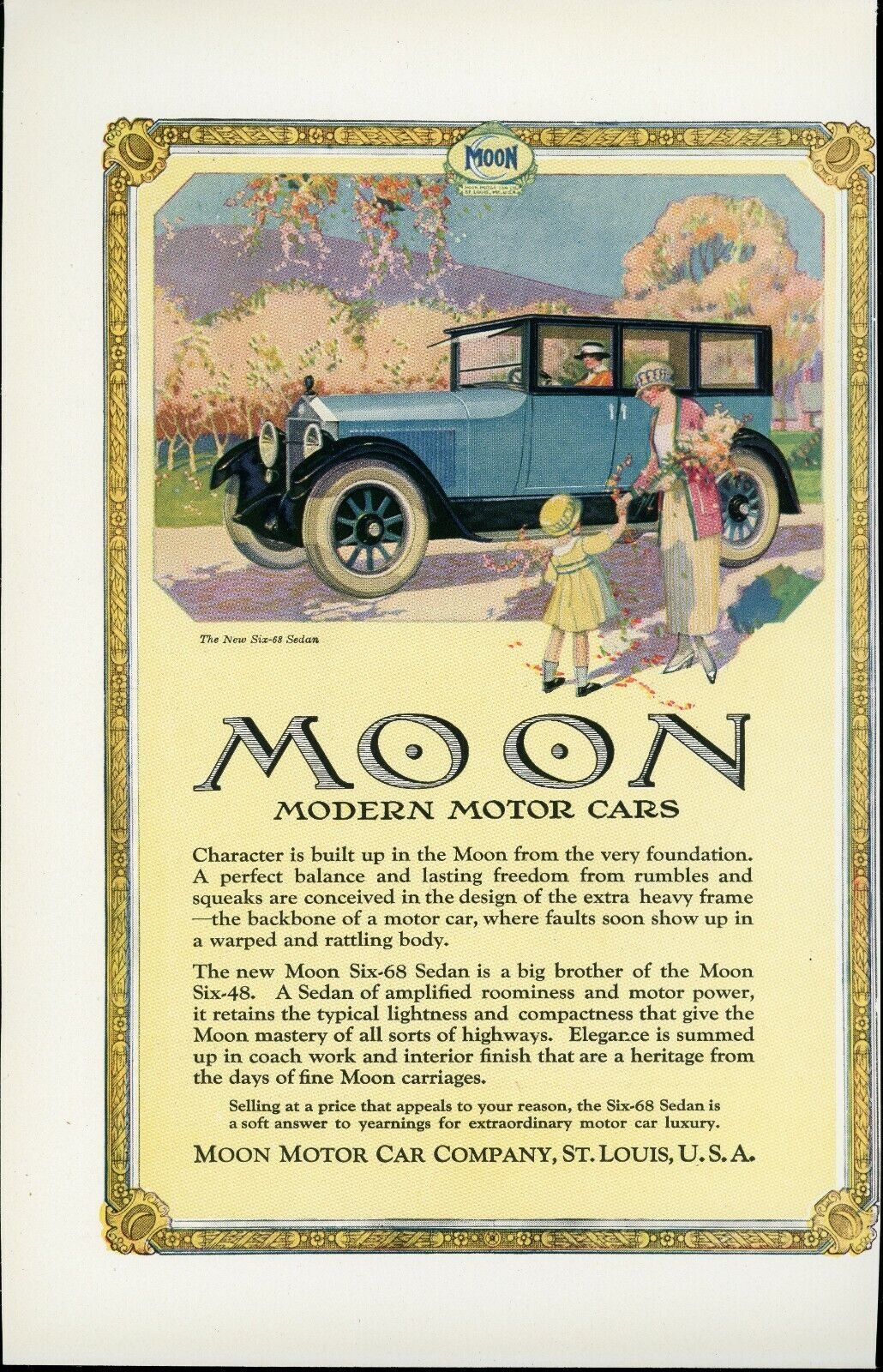

So, he launched a national advertising campaign that focused on the cars “style, comfort and color” that hid a well-engineered chassis. The campaign launched with full page advertisements in the Saturday Evening Post that had more than two million subscribers. To this he added a celebrity association when actress Clara Bow (left), Hollywood’s “it girl” at the time, one of the most popular actresses of the silent film era, agreed to a photo shoot with a Moon roadster.

The final chapter for Moon was a dramatic and tragic comedy of epic proportions. Archie Andrews was a swashbuckling opportunist and corporate raider unencumbered by ethics. He bamboozled William J. Muller, an engineer in the experimental department of the Edward G. Budd Company that had designed a revolutionary front wheel drive chassis, into giving him controlling interest of his innovative design.

He used this to solicit investors and secure loans in his newly minted New Era Motors. The envisioned front wheel drive car would be an expensive luxury vehicle named Ruxton. All that was missing a production facility.

Andrews, on the board of directors at Hupp Motor Car Company, was unable to have this company produce his car. Attempts to use New Era Motors to gain control of Marmon, Peerless, and Gardner failed. Then he turned to Moon, a company that had been plagued by declining sales just as the country was beginning its slide into the Great Depression.

It was a complicated arrangement but what Andrews orchestrated was a hostile take over of the company. The officers and directors at Moon attempted to halt the loss of control through legal channels. When that failed, they filed an appeal.

Andrews chose not to wait for a verdict from the court. He and hired thugs literally stormed the Moon offices. That company’s directors had barricaded themselves in the offices at Moon production facilities and made frantic calls to the court.

Suits and countersuits followed but meanwhile Andrews had control and curtailed production of Moon to focus resources on the Ruxton. Andrews had staged a similar attack on Hartford, Wisconsin based Kissel and planned to use that company’s recently modernized foundry and machine shop to produce transmissions and final drive assemblies. But rather than have their company fall prey to Andrews, the Kissel brothers filed bankruptcy, closed their doors, and liquidated assets.

Surprisingly the garishly painted cars were purportedly well engineered. Still, less than 100 Ruxton cars were built. But the onslaught of the Great Depression, Andrews legal fees from multiple lawsuits, and an inability to attract investors doomed the project. The Moon followed the Ruxton into oblivion, and obscurity.

Only nineteen Ruxton cars are known to have survived. One of these is proudly displayed at the National Transportation Museum off Route 66 just west of the city. The museum also preserves the history of the Moon, and an array of St. Louis automobile manufacturers.

Click on our link to Gilligans Route 66 tours to read about the exciting places to visit on this epic adventure planned and hosted by a New Zealand specialist.

Written by Jim Hinckley of Jim Hinckley’s America