Why India is limbering up as an electric powerhouse

/Just a fraction of its 1.4 billion population is driving, yet cities are already clogged, air quality is bad and most oil is imported. There’s gotta be a better way.

BECAUSE it’s until now been the sourcing point for just a few - sometimes oddball and often rudimentary - homegrown products, plus the occasional Suzuki and a low-rent Ford, the defunct EcoSport, Kiwis likely have the wrong idea about India’s role in global car-making.

More fool us. The sub-continent’s automotive industry is the world’s fourth largest by production and recently bumped out Japan to become the third largest in respect to sales, behind China and the United States.

It’s the fourth largest in respect to valuation of its automotive industry. Car and truck making’s worth is determined to be more than $NZ160 billion. The industry accounts for eight percent of the country's total exports and just over seven percent of India's GDP.

India enjoys a strong position in the global heavy vehicles market. It’s the world’s largest tractor producer, second-largest bus manufacturer and third-largest heavy truck manufacturer.

However, it’s with India’s annual production of passenger models where biggest change is expected to occur.

Future market growth is anticipated to be fuelled by new trends including the electrification of vehicles, mainly small passenger models that fulfil as the main component of a car market conservatively valued at $NZ60 billion.

India has a population of 1.4 billion but barely eight percent of Indian households own a vehicle. There are 22 cars per 1000 people.

Not a big count, you’d think, yet India’s roads are packed, to point where the cities this writer visited - Chennai, Pune and, especially, Mumbai, home to 22 million - are continually jammed. No journey at any time is ever swift. Taking two hours to clock barely 20 kilometres across the city before rush hour, always at nose-to-tail and largely at little more than walking pace, was a grind my hosts deemed pretty acceptable. Apparently it can get worse. Hard to imagine how.

Sobering stat: The country's population is expected to keep growing until the early 2060s. Cars are highly desirable status symbols and the growing middle class are especially keen buyers, so there’ll be more on roads barely capable of taking them.

It’s true India’s car market can be volatile. After 4.4 million vehicles were sold in 2018, volume plunged back below four million vehicles in 2019 as a result of a credit crunch and stayed that way until 2022, when the demand rose again. New sales last year came in at 4.25 million units. Japan’s came to 4.2 million.

What of 2023? More growth is anticipated, now that Covid is under control and the semiconductor shortage largely sorted. Plus, there’s the fizz of electricity in the air.

Most passenger vehicles sold in India have been petrol-fuelled, which includes some hybrid vehicles, but now it’s looking to fully battery cars, for all the usual reasons.

India mainly buys in its oil. The biggest current supplier has become Russia, so there are doubtless political reasons why it wants to reduce that dependence.

Yet climate change is as much an issue here as anywhere else. Southern India in summer is, of course, hot. But 39 degree peaks experienced in Chennai on the days this writer visited were considered disturbingly higher than average. It also desperately wants to improve air quality and has pledged to slash carbon emissions.

Currently, the transport sector accounts for 18 percent of total energy consumption in India, which translates to an estimated 94 million tons of oil-equivalent energy.

India wants to quit that habit. It is among a handful of signatories to a global electric vehicle commitment, EV30@30 campaign, which aims for at least 30 percent of vehicle sales to be electric by 2030.

As part of this, it has signed a memorandum of understanding with Australia to source crucial minerals: Copper, lithium, nickel and cobalt primarily.

Electrics accounted for 4.7 percent of overall passenger and light commercial volume in India last year. A modest penetration, perhaps, yet the sales counts is still huge.

India notched up a million electric vehicle sales last year, a leap of more than 300 percent from the around 320,000 units sold in 2021.

When India talks EV, it doesn’t just mean cars. A third of EVs sold in 2022 were electric three-wheelers.

Transition to electric mobility will be faster as car makers make big-ticket investments in the development of infrastructure to facilitate EV penetration in the country, industry experts expect.

“I am bullish about the EV market. Given the right impetus, rising EV adoption will create an immediate requirement to embrace the next-generation needs of the automotive industry,” Jaideep Wadhwa, director of Sterling Gtake E-Mobility, a motor control units' manufacturer for EVs, told the German news agency DW recently.

The global head of Mahindra Automobiles, Veejay Nakra, says incentives from national and state governments, and willingness from overseas investment funds to provide capital - in Mahindra’s case, $US145 million from Singapore-based global investment company Temasek announced on August 4 - are making it easier.

“From a focus of transition in the country from internal combustion engines, there is a significant focus to bring adoption of EVs into the country.

“We've taken that as an input into our strategy of the cycle of product development. Our estimates are that by 2030, about 30 percent of the Indian market will be EV penetration.”

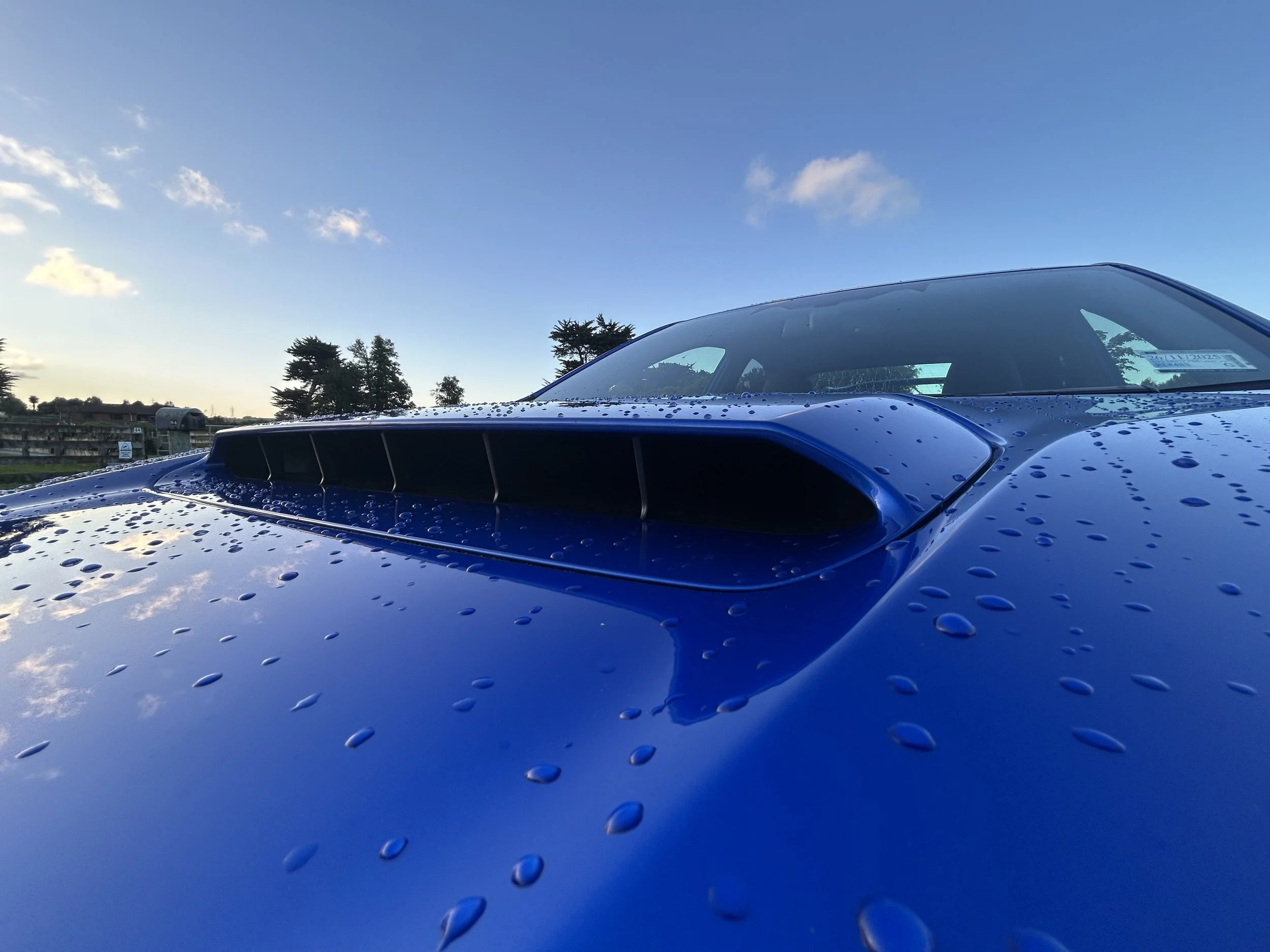

All Mahindra’s electrics will be “meant for India and the global markets.” It has one electric version of a car designed primarily for a combustion engine already on that. That model, the XUV400 (below), is coming to NZ. A battery-fed edition of the XUV700, that has represented here since March in front-drive petrol, is also coming.

However, the main thrust is with a new, bespoke electric product line developing under the ‘Born Electric’ mantle, using some components supplied by Volkswagen that underpin the German make’s MEB platform cars.

Says Nakra: “A lot of focus is going into EVs. December 2024 is when we will start the first product coming out on the Born Electric platform.”

The Economic Survey 2023, an annual document of India’s Finance Ministry, predicts India's domestic electric vehicle market will see a 49 percent compound annual growth rate between 2022 and 2030, with 10 million annual sales by 2030.

Additionally, the electric vehicle industry is projected to create around 50 million direct and indirect jobs in the next seven years.

Another independent study, by the Centre for Energy Finance, reckons the EV market in India will be a $NZ364 billion opportunity by the end of this decade if it maintains current progress to meet that ambitious 2030 target.

India’s Government’s commitment to EV includes a website which functions as a one-stop destination for all information on EVs and addresses concerns about the adoption of EVs and their purchase.

One challenge is to improve the quality and count of charging facility locations. At present the seventh largest country in the world, with a land mass of 3.2 million square kilometres, has 1640 of those (as opposed to 65,000 petrol stations).

Says Nakra: “I think they (the national government) understand the importance of creating a charging infrastructure ecosystem. There is a lot of work happening on that.”

The plan is to have 150,000 charging stations by 2027. India’s fuel suppliers are nationalised, so the idea is their petrol stations will also be EV-friendly.

“As in most countries there is a lot that happens between the support that comes in from the Government and the private sector (and) we also have a lot of startups in who are working in that area.

“It'll take some time to play out, but eventually it will. And it's also got to do with demand. They go hand-in-hand.”

As for consumer buy-in? Technology cost is reducing, and as energy density improves, so will range. India’s government offers EV purchase subsidies. A tax exemption of just under $NZ3000 is also given for people buying electric cars on loan.

The biggest feeder for car buying is India’s growing middle class; more families are enjoying double income earnings from both parents working.

As in NZ, sports utilities - which is all Mahindra builds - are increasingly popular; that type accounted for 56 percent of national new registrations in 2022. The compact to medium categories are the ultimate hotspots. In those segments, between 35 and 40 percent of buyers have not had a personal vehicle previously.

Intriguingly, while disposable income spending has grown considerably, outright cash deals for cars are not always assured.

It’s more common for first buyers in particular to take out finance over lengthy periods - seven year plans seem common - to buy a car.

How imperative is it for future electric Mahindras to be cost-competitive with current combustion engined types?

Nakra acknowledges “there is clear economics when it comes to the EV space.” That’s why Mahindra has become a leader in the three-wheeler category, with over 60 percent market share, he says.

Even so, there’s every reason why its SUVs are finding more homes, to point where the XUV700 has a domestic wait time of almost a year.

Desirability is strong, particularly post Covid. The virus appeared to awaken a desire to explore more. “Before Covid, small cars were popular. Since, it’s been all about SUVs.”

The demand is such that “many of them (new car buyers) are willing to stretch themselves to buy a product which offers them a lot more.” That’s an SUV.

“Many of the households now have got double income because both partners or spouses are working. So they are able to make that little bit of a stretch and … that's another reason why SUVs are the flavour. They see design, safety, technology, comfort space and say ‘it ticks all my boxes’.”

At present, India has more than 1.88 million registered EVs. Not bad in a country into which Tesla has yet to start selling anything, though that could soon change. Elon Musk’s outfit is in talks to build a gigafactory to produce the yet-to-be seen Model 2 compact hatch.

Does that worry the domestic brands? Nakra is guarded: “Look, at the end of the day, it's going to depend on the price at which they launch it in the country.

“They are definitely an aspirational brand, but I think it's going to depend on the price point at which they come in. We are pretty clear in terms of our (own) participation. It is going to be in more the large volume scale EV play, not necessarily at the top end premium category.”

As crucial as EVs are, India is also looking at other technologies. In addition to investing in EVs, conglomerates such as Reliance, Adani and Mahindra’s big domestic rival, Tata, are similarly investing green hydrogen and biofuels. Renewables and carbon capture and storage are also of high interest.

India’s mission is long-term. At last year’s COP26 conference in Glasgow, Scotland, it pledged to achieve net-zero emissions status by 2070.

The writer visited India as a guest of Mahindra Automotive, with travel, accommodation, meals and a small gift provided.