Experiencing Audi’s slide ruler

/Big controlled slides from a quattro? That takes some talent. Actually, no … not really. Not with the RS3.

AS a pukka competition, it’s heroic; as a late Friday night activity in a deserted industrial area, a headache – drifting treads a fine line between Ken Block-level hoonigan-ism and hooliganism.

All the same, car brands appear increasingly fascinated about how to make their cars chuck out and smoke up their rear tyres. Only select versions. All with stern factory ‘right place, right time’ warnings, of course.

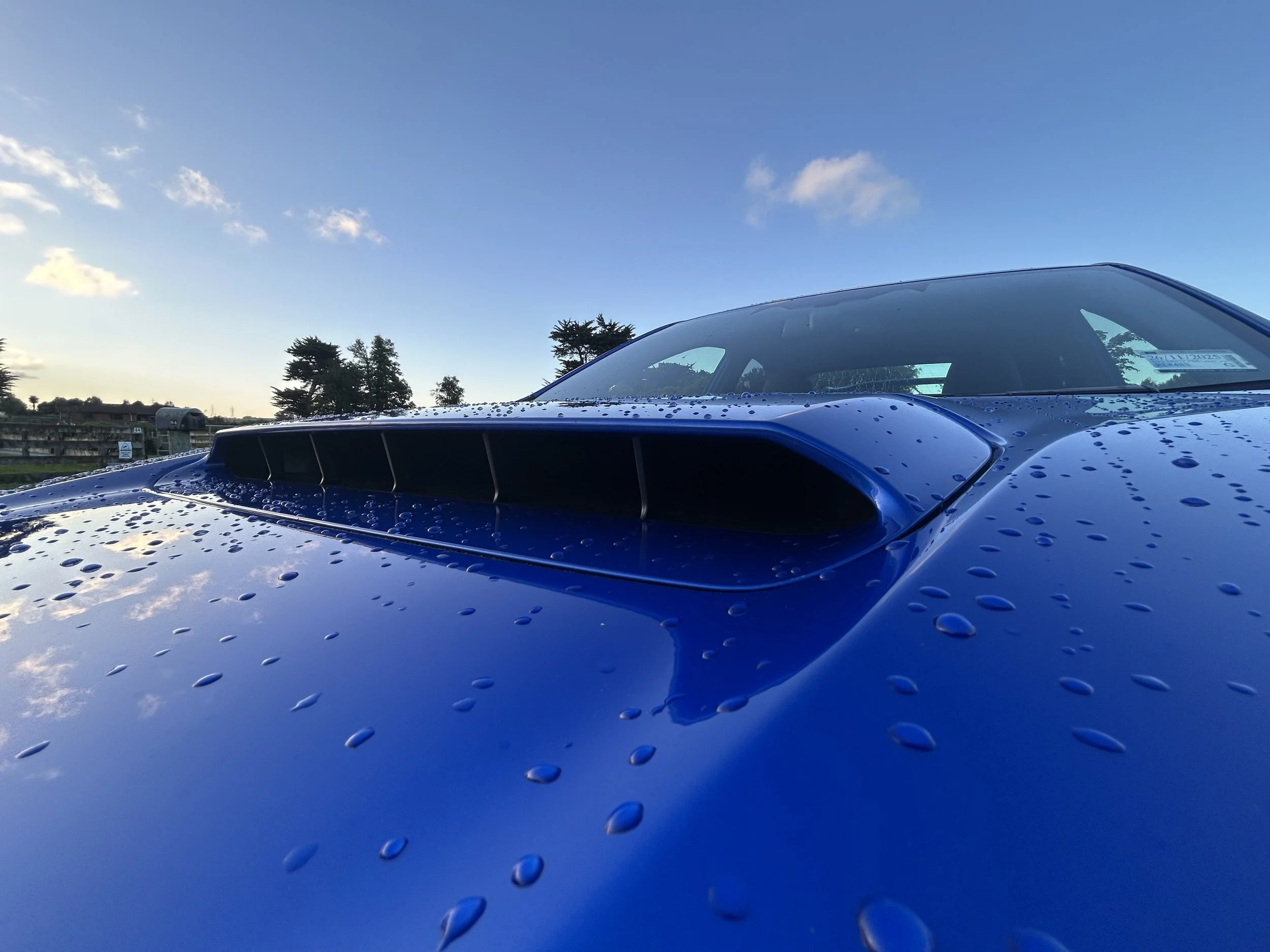

So to the Audi RS3 in its third generation, also odds-on the last to deliver with the fiery 2.5-litre petrol five-cylinder that has won world acclaim for more than a decade.

Rightly so; it’s a hugely characterful and highly-effective thing, with a fantastic soundtrack and impressive power and torque. This engine has spanned several RS products, but the one it has stayed with longest, Audi’s only true hot hatch, has been the one in which it is most celebrated. As it should be. It’s the perfect engine for the product, that, as a whole is an utter opus. Moreover, it’s an RS that seems perfect-sized and powered for NZ conditions.

No wonder 398 are in NZ ownership, that the 2022 consignment of 70 examples of the latest has been spoken for (out those, just under half have landed) and that Audi NZ is now trying to secure 30 more.

Driving a car is an acquired skill, but easy to learn so long as you take it seriously. Drifting, on the other hand, is far more difficult to learn. It’s fair to suggest you need to know how to drive before you can drift. Even then, skills needed in drifting are more complicated than the ones you need to start driving.

You also need the ‘right’ kind of car. Top of the list for start-outs is a rear-drive machine with decent wheelbase and a grunty engine. Never a front-drive. Remember, another word for drifting is ‘powersliding’. It’s all about losing traction in the rear wheels. Can’t do that in a car being pulled rather than pushed.

What about four-wheel-drive? You only need watch World Rally Championship action to see that all-paw scrabbling is possible, but due to obvious traction factors, it demands a special approach and incredible talent.

Conceivably, the previous two generations of RS3 could be drifted, but perhaps only in circumstances of extreme low adhesion. But, basically, their quattro was designed to defeat sliding and did so with such high effectiveness getting to … well, grip … with any kind of technique to beat it would require a lot of skill.

With the new one? Twenty minutes on from slipping behind the wheel yesterday, and after a series of simple and logical build-up exercises during which various electronic assist and enable functions were fine-tuned, I was getting the feisty little bugger into some full-out consecutive slides.

I didn’t quite manage to emulate experts’ ability to knock out a sequence of wholly enduring axis-to-axis skid around all four of the corners in the layout created for this test, but I think that with a couple more goes I’d have had a chance of achieving that ultimate feat.

As is, the ’10 out of 10’ for my best effort from my instructor Tim Martin left me chuffed. He’s principal of the Downforce driver training team Audi NZ uses; they’re the best in this business in this country and aren’t known for giving out easy compliments.

Of course, ultimate plaudits have to go to nameless VW Group engineers and programmers behind the car’s new, very trick new rear differential and the fresh-to-model-type dynamic and RS Performance driving modes.

The RS3 has always been a powerfully small stick of dynamite, but this is one with bigger bang. The engine makes more oomph than ever before and, yet, there’s ability now to loosen the reins quite a bit more. To the point where all semblance of civility disappears.

This RS3 has two ultimate RS setting. There’s RS Performance for race tracks and RS Torque Rear, what anyone else would simply call a drift mode. The first intends the car to remain tightly controllable at ludicrous speed and the other … erm … well, doesn’t. It’s all about tail-out action.

The core ingredient is a trick torque splitter differential, whose complexities are quite something else. Basically, there are a series of clutches and some very clever electronic activations that allow maximum torque to increasingly favour the rear wheels, the point of it being a rear-drive quattro. The talent goes further in RS Torque Rear; the system can ultimately divert all that twisting force to just one, with a theoretical 1750Nm feed (the engine itself outputs 500Nm, but there’s a multiplication factor).

The RS3 might well be the only Audi that achieves it – it’s really purely tuned for fossil-fuelled application; electrics can achieve much the same results, but with sensors - and it’s not an Ingolstadt-pure device. The Volkswagen Golf R arriving in a few weeks’ time has exactly the same thing, albeit married to a different engine (four-cylinder 2.0-litre engine, versus 2.5 five), though both action through the same direct shift transmission. Going on past pricing differentials, the Golf might be expected to be a less expensive avenue than this $112,900 RS3.

Audi enforces the public environment is emphatically not the place to play with the ultimate functionality. Our test area was the Lilyworld kart and drift track, a new addition for Auckland’s Mount Smart stadium. It’s a cosy arena, comprising, when drifting is involved, a serpentine sequence of a wide right into two tightening lefts, separated by a short straight, then two consecutive rights, also steering lock-reaching tight at anything less than skid speed.

The surface is fresh-laid tarmac (it used to be a carpark before the track was painted on) and was being liberally watered. As an integrity protection, the cars’ Pirelli P-Zero rear tyres were pumped to 50 Psi.

The most common way to drift is though what’s called the power over technique method. This means that you turn the car’s wheels to throw off its weight and give it an absolute boot full. That still applies with the Audi. How much occur from thereon depends on what traction setting is applied.

Downforce’s teaching regime was a prudent step-up. First came a sighting lap, simply to learn the layout, then a couple more at slightly brisk pace to get a feel for the car as it acts when all assists are engaging.

Things start to get interesting in Dynamic/RS Performance with stability control active; the car feels more agile, the engine more reactive and sounds louder. In the Sport ESC setting and RS Torque, the rear end kicks out but, even with right foot flat to the floor, it’ll only reach a certain, flamboyant slip angle. Session two is the deep end; RS Torque Rear mode with ESC off allows max torque to the rear and then out to the wheel on the outside of the curve. Yes, you can spin now. As I did halfway through my last run. How can you find limits without at least once exceeding them?

All our driving was in first gear, with entry speed of just under 30kmh and rarely seeing more than 40kmh. Obviously, it’d be more impressive with great speeds. But, well, there were walls and so on. A taste of the full-out potential came with riding shotgun with Andrew Waite, whose racing credentials are well known. His controlled drifts were well above mine, but I figure with a few more laps and latitude I could have come close. Maybe.

So what’s the point? Hard to say, really. As said, RS Torque Split is not a function you should ever contemplate using on the road. Realistically, it’s not that useful for circuit driving, either. RS Performance’s ability to keep the car neat and tidy when it’s being driven hard has to be superior. As impressive as showboating looks, hanging out the tail makes for slower lap times.

Still, you cannot blame the Germans for wanting to have a bit of fun now and again. And, assuredly, as drift features go, this is a good one. Certainly a lot easier to come to terms with that the mechanical set-up that came with the Focus RS, for instance.

As much as RS Torque Split really isn’t going to survive into Audi’s electric car immersion, the general concept obviously is.

Indeed, there’s already an e-tron with a drift function. That’s the e-tron S (above), the world’s first tri-motor electric car, which runs one motor for the front wheel set and a motor apiece on the rears.

The power is a highly credible 369kW but the torque is the headliner; a whopping 978Nm. That’s substantially more than the highest-powered non-S variant, the 55 quattro. In normal driving situations, only the rear motors are active. The front steps in when grip is lost.

There is a sport setting for the ESC and, when coupled with dynamic mode on the drive select, Audi says this EV can drift.

On completion of the RS3 event, I drove the e-tron S back to my home in Manawatu, in steadily worsening weather. The last 60 minutes of that almost eight hour (including replenishment stops) run was in teeming rain and the road was less adhesive than the track.

Theoretically conditions perfect for drifting, but way too risky to try. And there’s the reality of it, really.