Ford Escape PHEV review: Kapiti Island connection

/Ford’s plug-in Escape is the pathfinder in a big move by the Blue Oval to remove conventional internal combustion engines from its passenger vehicles.

Price: $66,990 ($61,240 with Clean Car rebate).

Powertrain and economy: 2.5-litre petrol engine with 88kW electric motor, 167kW and estimated 350Nm, CVT automatic, front-wheel drive, official combined economy 1.5 L/100km, CO2 33g/km.

Vital statistics: 4614mm long, 1675mm high, 2178mm wide, 2710mm wheelbase, luggage space 517-1423 litres.

For: Environmental champion; easy to operate, with electric power able to be saved for urban use.

Against: Price a little high, even with rebate factored in.

THE bright red compact SUV sat parked on the hard sand of Paraparaumu Beach - five kilometres across the water lay Kapiti, the island that for so many years has been an integral part of life along this portion of the North Island coastline.

I’d propose a connection between the vehicle and the island; as environmental champions.

Kapiti Island has been a nature reserve for 125 years, and today it is a bird sanctuary that is totally free of predators. A welcome change from a past that has seen it used for everything from whaling and farming, and even, incredibly, as a game reserve in which possums were introduced so they could be shot.

And the bright red SUV was a Ford Escape PHEV, a compact sports utility contributing to the electrification of New Zealand’s vehicle fleet. It claims an average fuel consumption of as low as 1.5 litres per 100km. A welcome change from its conventionally engined Escape siblings which are a bit notorious for using too much petrol.

I’d always wanted to visit Kapiti Island. For years, each time I’d driven to Wellington I’d seen it out there, a remnant of a mountain range that millions of years ago formed a land bridge that extended across what is now Cook Strait.

Maori are said to have occupied the island since the 12th Century, and for part of the past 200 years it suffered terribly at the hands of European colonisers.

At one stage more than 2000 people lived on Kapiti as five whaling stations operated to catch and process the whales that used to migrate through the Rauoterangi Channel between the island and the mainland. Then later in the 19th Century its eastern side was largely denuded of native vegetation and turned into farmland by various private owners.

But then – thankfully - in the 1890s the value of conservation began to be recognised. This led to the Government introducing the Kapiti Island Public Reserve Act in 1897, which aimed to protect the island.

“For the purposes of conserving the natural scenery of the said island, and providing a preserve for the fauna and flora of New Zealand,” read the Act, “it is desirable that the island should be acquired by Her Majesty as a public reserve, and that pending such acquisition all dealings therewith by private persons should be prohibited.”

This ban on future private ownership of any part of Kapiti soon saw various farms taken over by the Crown, and from 1906 the island had its own caretaker, various tree species began to be planted, and noxious animals began to be eradicated – goats were removed by 1928, cats by 1935, possums by 1986, and rats and ferrets by 1998.

All this means that today, Kapiti Island is a true sanctuary in all the best meanings of the word. The good news is that it remains publicly accessible too, although it is illegal for anyone to go to the island in private boats.

Instead, the number of people allowed to go to Kapiti is limited to 160 per day, and to get there they must first get a Department of Conservation permit and use operators that are authorised to take visitors to the island. These operators include members of the whanau that own the sole remaining privately-owned property on the island, and it is on this property that visitors can stay the night in luxury tents and cabins.

But we just went for the day – and that was intriguing enough. After climbing aboard the ferry which sat in its specially-built trailer on the sand at Paraparaumu Beach, we were soon reversed into the water and whisked across to the island.

There, following a briefing and talk on Kapiti’s history (did you know it was once New Zealand’s biggest export port?), we were left to wander through the bush and along the shoreline, experiencing the huge amount of birdlife on the island. Wonderful. One word of warning though: keep close dibs on your lunch, otherwise the kaka and weka are likely to pinch it!

Kapiti Island is an outstanding example of how our environment will reward us if we go to the effort of looking after it. The nation’s motorists are picking up on that too, which I am hopeful is a major reason why increasing numbers are buying vehicles with some form of electrification.

So far this year (to the end of November) 20,615 battery electric, plug-in hybrid and hybrid vehicles had been sold, which represented 13.4 percent of the total market. The trend is growing, too – in November this percentage had grown to 17.4 percent.

Personally, I still don’t think I’m ready to own a full EV – their range isn’t yet quite enough, and I can’t be bothered with the time taken to recharge batteries during journeys of any length.

But my family has owned a hybrid, and we loved the challenge and enjoyment that came with very low fuel consumptions and reduced exhaust emissions via careful driving. And, for our visit to Kapiti Island, we enjoyed being able to use one of the latest plug-in hybrids to enter the New Zealand market, the Escape PHEV.

It’s an impressive vehicle – and it’s the precursor of major changes about to happen with the Ford passenger vehicle fleet on offer in New Zealand.

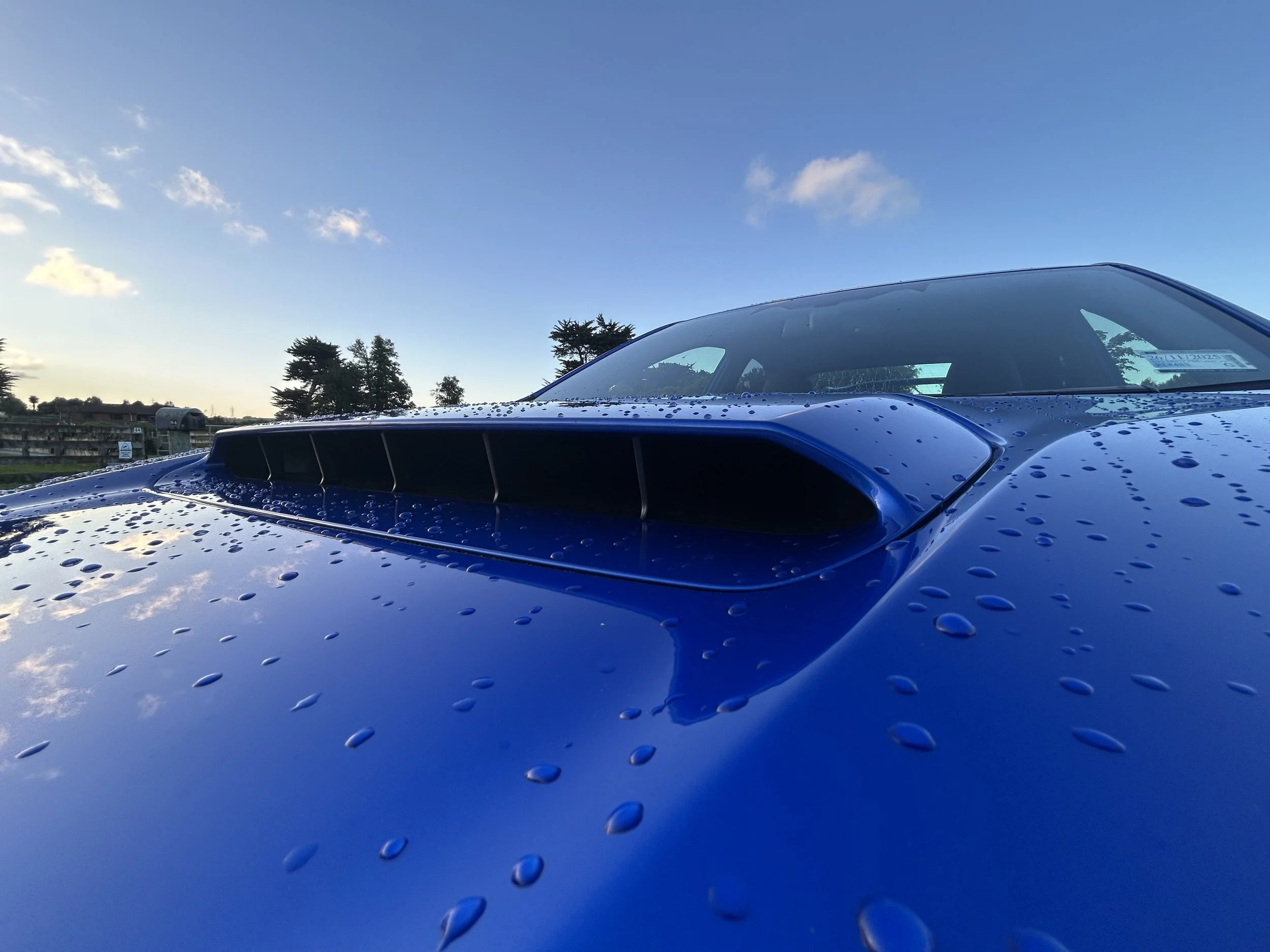

Identical in looks to the conventional petrol-engined model, the PHEV has a 2.5-litre Atkinson Cycle engine paired with an 88kW electric motor powered by a 14.4 kWh plug-in battery. This Escape’s total power output is 167kW and torque is estimated at around 350Nm, which is easily sufficient for a vehicle of this size – remember, this SUV is built off the platform of the Focus hatch.

Ford makes big claims regarding the vehicle’s economy. It says that thanks to its ability to operate purely as an EV for 59 km on a full charge, the Escape PHEV’s combined average fuel use is just 1.5 L/100km, and its CO2 emissions a mere 33 g/km. And that, says Ford, gives the SUV a range of close to 750km on a fully-charged battery and a full tank of fuel.

I quite believe the 1.5 L/100km is attainable during a normal working week in the urban environment, because the 59 km is easily the average commute and the Escape can be plugged in and recharged overnight.

But if a longer trip is factored into the equation? Nah…

I discovered during my 600km-plus drive to and from Kapiti that the consumption moves up to around 4.4 L/100km which in itself is still very good, considering that the top X-Line model we had for test weighs in at 1843kg. That level of fuel use is at least half that of the conventional ICE model.

What I did enjoy about the vehicle was its rotary dial on the centre console which can be used to select four EV settings – EV Auto which leaves it to the Escape to decide how to use its motive power, EV Now which prioritises pure electric operation, EV Later which holds battery charge until the driver decides the Escape should operate as an EV, and EV Charge during which the petrol engine replenishes the battery.

On start-up the system automatically defaults to EV Auto, which makes sense considering the PHEV is primarily a petrol-electric hybrid vehicle. And I figure the EV Later setting is a nod to cities in Europe where there are strict exhaust emission controls regarding vehicle use in congested urban zones – when you entered such zones, you’d simply switch things to EV Now.

I found myself having fun using the EV Charge setting on the open road, then switching to EV Now when entering every area with a 50kmh speed limit. It was easy to operate – a very good operational design feature from Ford.

Maybe that’s the best way to describe the Escape PHEV itself: its ease of operation.

It’s a simple task to park the vehicle overnight and charge it by plugging it into a normal domestic power supply, where the battery will fully charge in a maximum of six hours – and little LED lights surrounding the Escape’s charging plug point tell you the state of charge.

It’s a simple task to drive the vehicle, too. You can leave it to the on-board computer wizardry to decide how the hybrid system should operate, or you can take over the operation by using that very good EV button.

Although the Escape PHEV is quite heavy, it feels light enough and its handling characteristics are secure thanks to a sports-oriented suspension. At the X-Line level of specification it is comfortable and well appointed, with standard items including a panoramic sunroof, Bang and Olufsen audio, heated seats, hands-free tailgate, 12-inch LED instrument cluster, and 19-inch alloys.

Ford Escape has been around for more than two decades now – although for a while there it found itself being called Kuga – and up until now its primary power source has been the conventional petrol-fuelled internal combustion engine.

But things are rapidly changing with this fourth-generation version. The ICE models were introduced almost two years ago to critical acclaim, but now the PHEV versions are on the market and they are clearly superior product.

Two versions are available, the entry model at $60,990 and the X-Line at $66,990. Both qualify for the Government’s $5750 clean car rebate which, in the case of the X-Line we drove, brings the price down to $5250 more than the ICE equivalent. Given the PHEV’s excellent fuel economy, it wouldn’t take too long to cut out that price premium via lowered fuel costs.

Early next year the Escape fleet is to be joined by four hybrid models, which will be offered with a choice of front-wheel drive and all-wheel drive. While nothing has yet been officially announced, the arrival of the hybrids will spell the end of the ICE models – and the same will apply to Puma and Focus.