Electric dream path now less certain?

/Government’s easing of environmental standards will supposedly be beneficial to buyers, but what good will really come of it?

COLLAPSED consumer interest in new electric cars has been notified as a reason why the Government is now reshaping regulations designed to progressively clean up emissions from vehicles.

Intents announced yesterday are the Government’s second look in 14 months at the Clean Car Standard (CCS), a regulation that under its instigator, the previous Labour Government, was achieving aim of reducing CO2 count from new cars but under the current National-led coalition is not.

The logic of CCS is simple. It charges importers for vehicles that have CO₂ emissions-to-weight ratios above a certain target, with credits for vehicles with ratios below that target.

Introduced by the previous Labour Government in 2023, it was a huge step toward cleaning up emissions - but, increasingly, that looks like being a forlorn hope for those who understand the importance of that goal.

The country has gone from a state of being just ahead of the CCS reduction targets, which were to progressively toughen all the more from this year onward, to falling further behind.

The change of climate, so to speak, ties directly back to reduced interest in electric cars - a state the current administration largely triggered.

It first dropped the penalties buyers felt directly when buying high emissions product, under a system called Clean Car Discount, then also pulling a rebate to incentivise uptake of fully and heavily (plug-in hybrid) electric cars.

Claim then about the rebate being abused and that the penalties were hindering uptake of diesel one-tonne utes important to work place and rural NZ were tenuous - for instance, all through CCD the Ford Ranger held the same No.1 status it retains now, while the Toyota Hilux also remained strong.

Under the current administration, Kiwis have bought more strongly into hybrid cars - which use electric modestly and still always rely on petrol, so only show relatively modest emissions improvements - and have reverted back to higher consumption models.

Utes - at least in their primary diesel formats - fail to meet CCS expectations, even after it was relaxed.

What trends might further evidence with the Government’s next intent, to slash CCS charges by nearly 80 percent, is anyone’s guess, but it will hardly benefit the Green intent.

The new vehicle industry, which was once a strong supporter of CCS and even accepted CCD, though not without grumble, has all but u-turned on its views, simply because it always made clear that in order to work the strategy required a strong political ambition.

If politicians in charge lacked conviction about climate issues and why reducing exhaust nasties from vehicles is so vital - as seems the case - why would the public care?

The scenario for CCS now is that motivation to reach loftier eco-friendly targets will become more a personal choice, and less one that is required by mandate.

Charges will drop from a top rate of $67.50 to $15 per gram of C02 for new vehicles, and from $33.75 to $7.50 for used vehicles, for 2026 and 2027.

Government says this will prevent vehicle price increases that could have cumulatively cost consumers hundreds of millions of dollars. What it doesn’t say is how much it will alter, for the worse, the average CO2 output, which since the last election has been tracking upward, having been in decline prior.

The changes certainly advantage higher CO2 vehicles, industry specialists note.

As examples of potential savings - the XLT Double Cab version of NZ’s best-selling one tonne utility, the Ford Ranger, could see $315 reduced, a Toyota Hilux SR5 Cruiser up to $1050, a Ford Everest Platinum 3.0D $6825 and a Mitsubishi ASX LS 2.0 petrol up to $4725, again at most.

None of those vehicles are exemplars of eco goodness; the Fords and Toyota use diesels whose smut levels run from average to high (Everest’s V6) ad the ASX uses one of the oldest petrol engines on the market.

Tellingly, too, in relating positives savings for those products, Government nimbly sidesteps explaining that another repercussion of this revision is the potential for some EVs that presently seem attractively priced to become a little less so.

While the changes are expected to pass Parliament this week, they will not come into effect until January 1 - will intending buyers hold off on their purchases until then?

Government estimates the changes will avoid $264 million in net charges that could have been passed onto consumers through higher vehicle prices. It also sees less pressure on importers which in turn will keep cars affordable.

It’s an adjunct to argument to one mounted in July, 2024, when it began watering down the ordinance arguing it was too strict for car importers.

At that point it also decided to align align CO2 emissions standards with Australia - saying that change would strike the right balance between reducing transport emissions and ensuring vehicles would be affordable.

Now Transport Minister Chris Bishop says most importers are unable to meet the targets under the scheme as it currently stands - an argument that has the support of the Motor Industry Association (MIA), a body representing most distributors.

The MIA says new car prices would have risen sharply, and some models would have been withdrawn, had CCS continued as is.

That doesn’t mean prices won’t rise nonetheless - currency pressure is being felt, also, notably against the US dollar, Japanese Yen and the Euro.

Again, much of what’s happening now bases on changing consumer habit of the past 18 months, most notably the drop-off in interest in the the types most needed in circulation because they emit no CO2 and earn credits to offset the penalties applying to many of those that do.

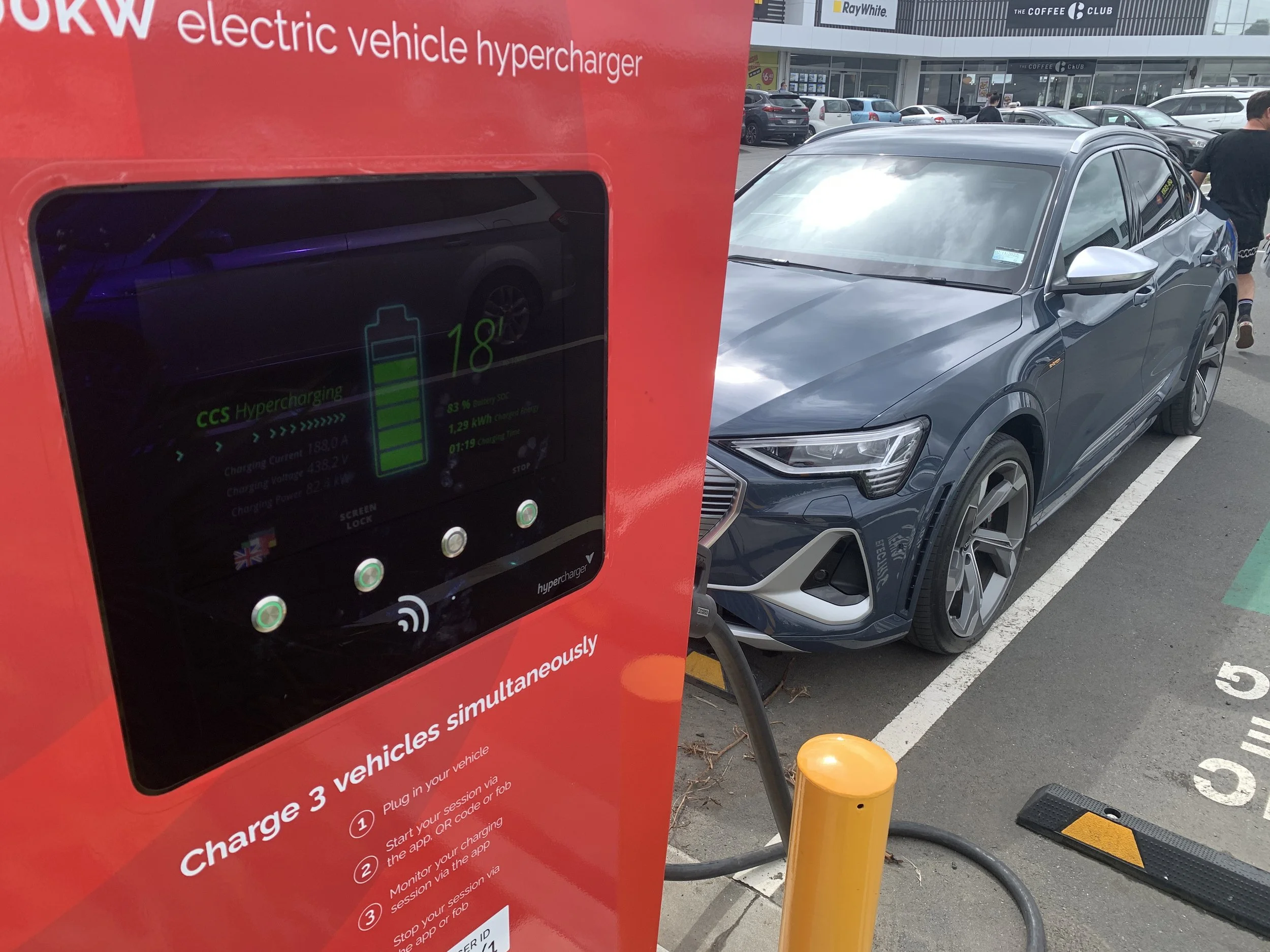

The EV interest decline began the moment the current administration pulled rebates on EVs costing $80,000 or less. It intensified when all were hit with Road User Charges, a long-planned initiative.

Basically all kinds of fully electric models, regardless of being eligibility or otherwise for the rebate, have since lost favour.

This even though prices have fallen - in the last fortnight the first new EV choices under $30,000 rolled out. It means NZ has fallen from its place, held between 2020 to end of 2023, of being a country of particularly strong EV interest to an also-ran.

Last month, just over 500 were registered - a count well short of the interest that occurred at peak of popularity.

That has coloured distributor decisions. While Chinese brands new to the market are looking to establish with those products - mainly because EV and plug-in hybrid is now a speciality of China’s car industry and its export push - others have quietly begun to reduce their choices or simply delay introductions.

The latest decisions might well dismay electric vehicle supporters, and those involved in providing infrastructure.

Bishop acknowledges CCS has helped lift fuel efficiency, but now the market conditions had changed, with a supply shortage of cleaner used vehicles, and a drop in demand for new EVs.

"Most importers are now unable to meet the passenger-vehicle targets,” he said at a media briefing

“In fact, right now, 86 per cent of importers are facing a net charge rather than net savings from credits. The scheme is so out-of-whack with reality that even some hybrid vehicles will attract charges rather than credits.”

CCS CO2 targets were set to decrease each year until 2029, while the charges for exceeding them would increase. Credits will be protected so that none expire before 31 December 2028, while the standard is reviewed.

MIA view is that CCS stopped working because as much as it pushed EV supply forward rapidly, consumers had not shifted at the same pace. The gap has continued to widen, it says

Expectation from CCS when it it enacted was that, in 2025, one in every five new light passenger vehicles would be electric. Actual sales this year are closer to one in every 10.

The MIA says it becomes very simple: Importers cannot earn credits when customers are not buying the vehicles that create them. This forces many into costly credit purchases or penalties.

“At $67.50 per gram of carbon dioxide, industry forecasts show compliance costs are likely to total around $125 million in 2025, rising to around $153 million in 2026,” MIA chief executive Aimee Wiley noted.

The MIA says none of that funding goes to Government or to emissions reduction initiatives. Rather, it circulates between companies and is ultimately transferred offshore.

“This became a costly compliance market rather than a policy that reduced emissions,” said Wiley.

“Importers unable to earn enough credits have been drained financially, putting vehicle prices at risk and limiting the ability to invest in the technologies that genuinely lower emissions.”

It said while hybrids sit between traditional petrol and diesel vehicles and zero emission models, the consumer swing toward them cannot be ignored. Public sentiment was that this technology offered certainty, fuel savings and practical benefits.

Had CCS kept tracking as planned, many hybrids would attract penalties from 2026 - a consequence of them not being as eco-friendly as perception would have it.

The MIA note that, with a large share of the market in the hybrid category and low uptake of electric vehicles expected to

continue, the gap between the targets and real-world behaviour is widening.

It’s argument that EVs remain more expensive upfront is not untrue. The discounts of last year were a oncer, and while some new products have become cheaper (and in the fortnight two have broken into the sub-$30,000 zone once the domain of small thrifty petrols), the larger, most range effective products that were subject to fire sale last year have all returned to original RRPs, most above the average spend.

Concerns about range have eased and charging availability is also improved, but total cost of ownership question is flavoured by very poor residual values. Sometimes the technology itself reaches too far.

Argument that regulation cannot force consumers to buy a vehicle they do not want or cannot afford is one that will be contested either way. But, as Wiley says: “When policy pushes supply in one direction but demand does not follow, strain becomes severe.

“Prices rise. Choice shrinks. Businesses face increasing costs. Consumers ultimately carry the burden.”

She says this is what has been happening, and would have continued to happen without intervention.

“Vehicle prices would likely have risen sharply in the months ahead and many affordable models would have disappeared from the market, while emissions remained largely unchanged.”

The MIA plans to work with Government to design a simpler and more effective Clean Vehicle Standard, version two.

Wiley says the goal is a framework that remains ambitious in intent while being grounded in real world demand, supporting customer choice and delivering measurable emissions reductions over time.

She says the industry is not stepping back from environmental goals.

“We are repairing a system that was costing New Zealand hundreds of millions of dollars without reducing emissions. This is climate action that will work.”