GWM Cannon Alpha Lux PHEV road test review: Bright spark

/The ute sector’s diesel addiction is obvious, but now there’s another way.

How much: $64,990 (until October).

Engine: 1998cc four-cylinder petrol engine with gearbox-integrated electric motor and mains-replenished 37.1kWh battery; 300kW/750Nm combined; four-wheel-drive; nine-speed automatic.

Dimensions: Length, 5445mm; width, 1991mm; height, 1924mm.

We like: That it exists; that it fulfils primary functions; fewer safety assist annoyances now.

Not so much: Clumsy spare wheel location; some ergonomic annoyances; cheap key fob.

THIS time last year the plug-in hybrid ute category existed locally in concept only - now there are three working the beat, who knows how many more are en route?

With diesel so dominant, it’s hard to yet see this technology kicking off a coupe d’état in the one tonne ranks quite yet, if ever.

But who really knows? The ute category has already changed so much these past couple of decades. Yesteryear’s basic beats of burden have become so much plusher, more powerful, more family and fun-focused now.

Anyway, the plug-in petrol push is on and already there seems to a clear contender for top trumps status.

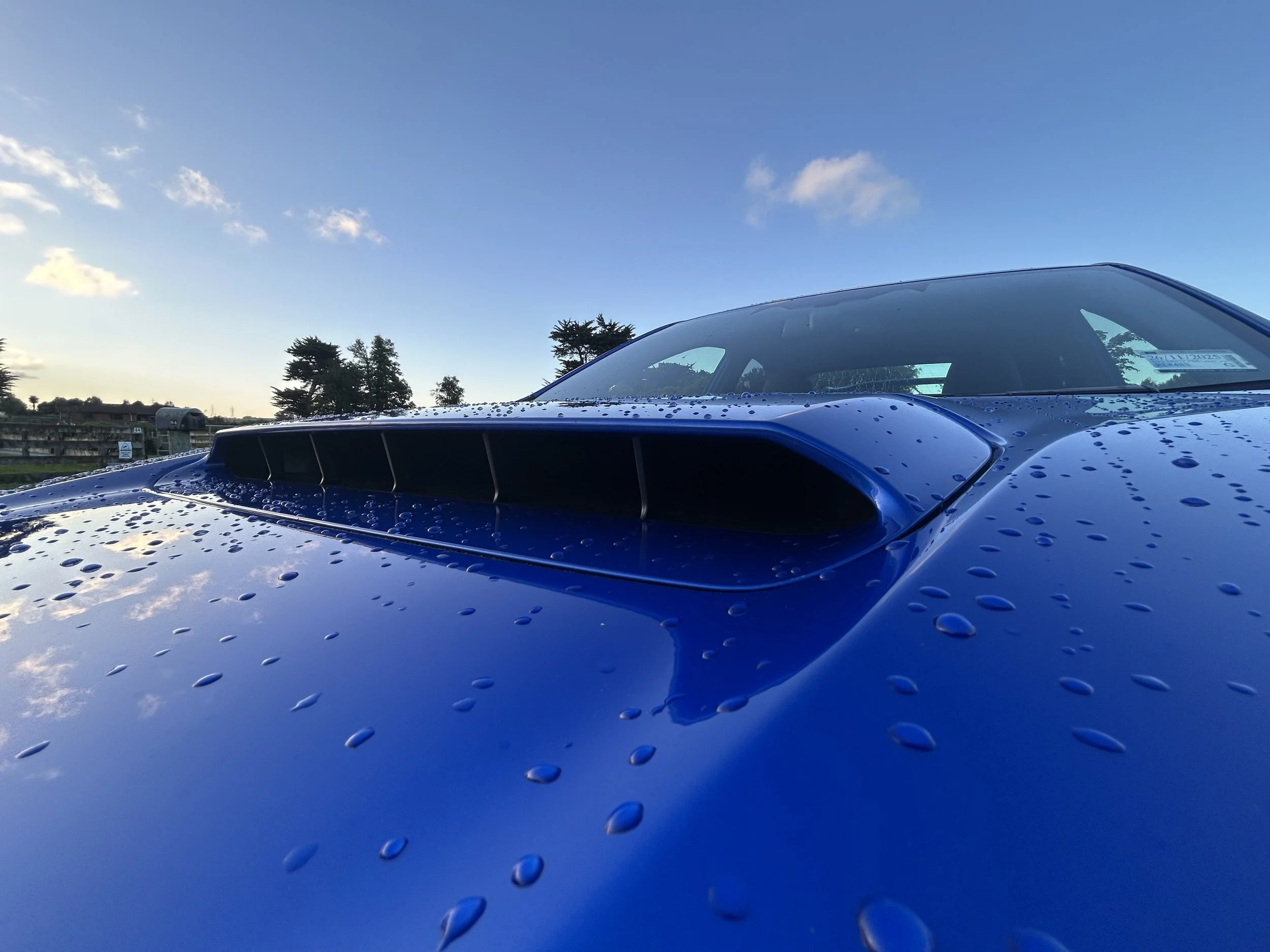

Simply by going larger in dimension than any only contender in its category has made the Cannon Alpha a stand-out in the ute selection for some time now.

But more than being a bigger and bolder choice than the regular Cannon it joined several years ago, China's kingpin also become the GWM model at forefront of a technology push.

That it first showed in diesel was simply to establish an initial market position. Even then, the ideal was to stake out as something special by breaking into new territory. Hence, the next step of a closed loop/mild petrol hybrid. That in itself was something new to consider and a bit daring; yet it was also just a transition toward more aggressive electrification.

What’s come out now is far more radical; still hybrid, but reliant far more still on electric assist, to point it carries a super-large battery that replenishes off the mains.

As much as we’ve become used to PHEV in passenger cars, finding it in a ute is quite a thing to get your head around.

Chances are, rural stalwarts will always resist. But that’s hardly going to be a concern here. The entry Cannon is the one for mucking in down on the farm; the Alpha, on the other hand, has always aimed more directly at appealing to those with upscale lifestyle tastes.

Bigger, bolder, better equipped. That’s the GWM mantra with this vehicle in its already established formats. The Alpha PHEV simply continues that ethos.

As said, there are just two rivals on this turf. It straight out overshadows the like-minded BYD Shark and Ford Ranger PHEV alternates for physical dimension, muscularity and electric-pure range. It has the biggest battery, seems solid at proper off-roading, holds a top trumps tow rating and has released in a strong pricing position.

All that could well help it sell to the person who is a first time ute intender out to steer down a new technology path.

However, that’s a niche audience. To be fully useful to GWM’s bottom line, it needs to win over a much tougher crowd.

Allegiance to diesel is strong. What will it have to do to win over the black-hearted?

A week of driving enforced how close it comes to emulating what you'd expect from a four-wheel-drive diesel ute, on seal and beyond. But it also revealed that efficiencies stated by the brand are not to be taken too seriously. The overall economy return on this test was close to being diesel-like, but failed to evidence as diesel-beating.

Even so, it’s an exciting an intriguing technology advancement proving, for one, that the idea of slotting a 2.0-litre turbocharged petrol engine into a ute this size isn’t the big call it might seem, because of the electric ingredient.

The combined influence not only greater than GWM achieves with the mild hybrid Cannon but also makes more power than some diesels and enough torque to stand tall as well.

The electric motor is solid, the battery that feeds it substantial. At 37.1kWh, it’s of a capacity Nissan believed was sufficient for the Leaf until recently.

Still, the ’fire it up and go’ simplicity that sells a diesel isn’t quite replicated here. Sure, you can simply take that approach when driving the PHEV, but outcomes when left entirely to its own devices could well be more tempered than those arriving as result of taking the time to understand how the brand hopes you will work it.

Ideally, it expects an operator to be in the mood for using the EV, HEV and Smart/Intelligent modes.

Depending on the state of battery, this can be a fully electric machine or an assisted petrol. Or it can be a petrol-driven vehicle that, at same time, is using the engine to replenish the battery.

Take-offs are consistently on battery-fed impetus. At urban pace, you can be lulled lulled into thinking of it as an electric vehicle that relies on combustion power as a backup. And, if kept in EV, it will genuinely drive at open road speed without the engine. For a while.

Ultimately, of course, it still needs combustion assistance. The more you ask of it and the further you take it, the more the petrol-prioritisation, and not just for turning the wheels. It harvests power under braking, but more comes from the engine acting as a generator.

GWM claims of combined fuel consumption of 1.7L/100km with a full battery. That would allow a theoretical 1060km total range if presuming, unrealistically, that you’re prepared to fully recharge the battery after every 100kms of travel.

They also say it can deliver 7.9L/100km with the battery at a low state of charge. And then there’s the added appeal of 115 kilometres’ pure electric running.

It makes make fabulous reading, but most of the values come from using the NEDC scale, which has been widely discredited, to point it’ll soon be unacceptable here. The preferred WLTP scale still suggest best-state frugality of 1.9L/100km, but also diminishes the electric pure opportunity to 90 kilometres.

This test? The vehicle was not mollycoddled. Cannon’s trip computer isn’t the easiest to fathom, but it suggested an overall average from more than 400kms’ driving of 10.8 litres of dino-sauce per 100km and 2.6kWh/100km energy consumption, and an average of 35kWh/100km on EV-only mode.

That sort of fuel burn is akin to that often seen from a diesel ute,. Again, though, it needs reinforcing that the Cannon is big and, in this state, heavy.

At just shy of three tonnes, the PHEV carts several hundred kilos more than the comparable hybrid, which in itself is a touch porkier than some diesels.

And it’s a chunky thing in all forms. Width is class usual, but it’s almost American in height and length. In urban situations, you’re acutely aware of the latter, especially when the tail sticks out in angle parking.

Commensurately, it has a ‘king of the road’ air that brings a commanding view and a cabin with plenty of room up front, and although taller back-seat passengers will appreciate the recess in the headlining to sit comfortably, they get decent leg room.

It purely conforms in the market-preferred dual cab with drive to all four wheels via a nine-speed automatic transmission. The wellside bed is a square floor with high sides to deliver good space, though the spare wheel being mounted in there might become a point of frustration.

My time reinforced it conforms to the same strength that every PHEV evidences. Driving short distances and replenishing the battery daily is a winning formula.

Also, there’s logic to prioritising EV purity for urban use and slow speed off-roading - where electric can deliver an enviable accuracy - then reverting primarily into HEV for general mud-plugging and any open road running, no matter how short that distance.

HEV brings in petrol, but also keeps good relations with the battery-fed side. I used that on a long drive and saw good results, down to around 6.2 L/100km indicated.

However, the peak benefit didn’t last for all that long. I’d pretty much exhausted all the goodness 120kms of a 210km run (I hadn’t begun with a fully charged battery).

For the remainder of that drive, I adopted Smart/Intelligent, which not only optimises the engine for driving, but also - when the set-up determines it is practicable - to become a generator to replenish the battery.

It still pulled strongly, but a clear change to the engine note was obvious. Prior to that state, it was already signalling a different kind of aptitude than a diesel.

Insofar that while it clearly has lots of torque at low revs, it doesn’t wallop it it with quite same oomph that you get with compression ignition and there’s more keenness to kick down when accelerating. Still, the transmission is very refined so even if it drops two or sometimes three gears to maintain impetus, it does so without being jerky.

What also impresses is how neatly the new way synchs into the basic functionality of this model. Utes about about utility; four-wheel-drive types are about workhorse practicality. The PHEV fulfils those functions.

On seal, the four-wheel-drive system will only engage fully when the electronics sense a loss of grip, the intent being to boost fuel efficiency in everyday driving.

The all-out off-road functions are all activated at the push of a button. Provision of a high- and low-range gearing, and a locking differential is not to be underestimated.

In both PHEV formats you have the same 224mm of ground clearance as the regular Cannon. Same 800mm of wading depth capability too. In respect to water immersion, the batteries have also been given an IP67 water resistance rating. To achieve this, they needed to survive 30 minutes of submersion in one-metre of water.

The diesel and mild hybrid Cannon have leaf-sprung rear suspension, the PHEV (to fit the battery) goes to an independent rear. It’s prone to lift a leg more easily, but realistically the road-tuned ‘Giti Xross’ tyres will become the primary weakness in muck, though in this instance on-farm work was no issue.

The ute-standard 3500kg towing rating also carrying over for the PHEV is a big inducement. How good? Who knows. Frustratingly, the tester lacked a tow bar. In hindsight, perhaps this was the distributor quietly seeking to self-protect against potential issues. The vehicle’s own mass raises prospect you’ll need a truck licence to haul anything of substance legally.

It’s also not a one-tonne ute in sense that the wellside weight limit drops to 685kg, which is more modest than the also weight-restricted hybrid and well off what most diesel utes will deliver. That’s possibly not going to inhibit general weekend warrior use, all the same.

However, the big faff is the spare wheel’s location. On the diesel and mild hybrid Alphas, it’s tucked under the deck. But that’s a space required for the PHEV’s battery, so they’ve had to think laterally.

I agree with the proposal that any vehicle designed for work and off-roading application should carry a spare. But as much as GWM’s intentions are good, it’s ‘solution’ here - siting the spare in a cradle on the driver’s side of the wellside - is a poor concept. Most patently, it clearly inhibits fitting a canopy; beyond that, it just restricts how you use what is a practically-sized load area.

In any event, in my instance, another issue arose. The spare comes with a vinyl cover, but I wonder how long it will keep this?

Had I not seen a movement in the rear view mirror, the one on this example would have torn off in the slipstream first time I drove into a 100kmh zone. On scrutiny of how it poorly it affixes, with two plastic clips and some magnetic tabs, I’m surprised it didn’t dislodge earlier. I didn’t chance a repeat so stowed it in the back seat.

The spare itself subsequently also came off and, ultimately, the cradle followed. That was because Mrs B wanted me to pick up some garden mulch from a local supplier. He uses a loader and I figured the spare would get in the way, so out it came. On cleaning down the deck after the home improvement job was done, I discovered a lot of muck was stuck under the cradle., held down by eight hex-headed bolts. Fortunately, I had the right tool. Removal and reinstatement for a clean up that took but seconds was a half hour job.

One factor from taking off the spare was how it altered the ride quality. The battery’s extra weight in itself seems to lend the PHEV a more settled ride than the other versions, but only to a point. You can feel the front end bounce and jiggle at low speeds and, like the regular kind, extra kilos in the rear settles it down. The spare is heavy and it alone made a difference. Still, on corrugated gravel for one, the PHEV felt more smooth and controlled than the alternate edition.

Refuelling means ensuring the left flank closest to the pump; replenishing asks you ensure a public charging cable can reach the right side. A 50kW fast charger is a good choice, as that’s it’s peak replenishment rate, with 30 to 80 percent fast charge in 26 minutes.

AC home charging means pulling out the factory-provisioned cable; you’ll find it stowed behind the rear seat. This is at up to 6.6kW, so a full charge requires being hooked up for 6.5 hours.

The potential for vehicle-to-load technology that allows powering external electrical devices at up to 3.3kW sounds attractive, given that’s a big sales point for Ranger, and it being configured for an app, which opens up remote functions like climate controls, location and locking/unlocking through your smartphone sounds really enticing, too.

However, neither are as they seem. The app is only useful for full ownership, not road testing, and after searching for a household plug (starting with the deck, as that’s where Ford places theirs) proved pointless, I discovered it’s another PHEV that uses a special power board that plugs into the charging port. This costs extra.

Inside everything looks very premium and there’s a solid span of comfort and convenience features, yet fit and finish isn’t quite to class best, the seats aren’t all that shapely and some design elements are a bit OTT, no more so than the gear selector. Also, the key fob is super nasty; you’d mistake it for a cut-price garage door opener bought from Temu.

The base grade has LED lights, a 12.3-inch touchscreen, fake leather upholstery, a full suite of safety systems. Including in the assists is a 360-degree camera system, along with parking sensors front and rear, which you'll be depending on.

The fit out seems tasty enough … until you see how much more swag the Ultra implements for an additional $7000. Stick with the Lux and you miss out on heated and ventilated front seats, and rear outboard seats, massaging front seats with memory, a head-up display, interior ambient lighting, 10-speaker sound system, front and rear wireless charging pads and a panoramic sunroof. Though both kinds have a sliding and reclining second row, that function being electric in the Ultra trim makes it more rewarding. The Ultra also has the niftier kind of tailgate.

The GWM has a large digital instrument cluster, which allows the driver to go through a variety of functions, views and readouts, some easier to access than others.

Same goes for the infotainment. Hook up to Apple CarPlay and the screen will dedicate itself wholly to that display, but in doing so you lose instant access to the climate control. There’s a bank of buttons below for quick functions, but not for full control of the system. In respect to controls, there’s no physical volume dial. You can adjust it from the steering wheel (which is clearly inaccessible to a passenger) or going into a screen menu, which is a faff.

GWM’s driver assist ingredients run to autonomous emergency braking, blind-spot monitoring and a lane-departure warning system that includes lane-keep assistance and centring. There's also a driver fatigue monitor in both vehicles, which operates via a camera mounted on the A-pillar.

Criticism last year of these being over-reactive caused GWM to effect some significant re-programming, notably to the speed recognition, emergency braking and lane keep functions.

The PHEV was the first of the improved models I’ve tried and, yes, it’s far more tolerable. Sure, it still cannot resist the occasional false positive, but overall is so much better.

Diesel is strong, but the Cannon PHEV at least offers a genuinely thoughtful alternative. How it ultimately does for running cost might require some careful mathematics, all the same, and you wonder about Road User Charge. It’s become detrimental to PHEV passenger buy-in but has never restricted utes … will this tech be a litmus test?